Reading Time: 5 minutes

There are a number of “tricks of the trade” commonly used by rogainers and orienteers, that are useful when bushwalking or ski touring too.

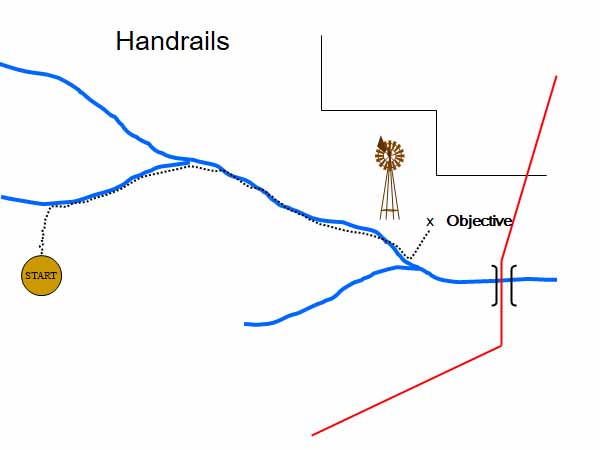

Handrails

Bushwalkers use handrails most of the time because most bushwalking takes place on tracks. A track is an example of a handrail.

Tracks aside, when off-track walking, navigators are always on the lookout for handrails because they usually make for easier navigation. A handrail is a definite linear feature such as a well-defined spur or ridge, a fenceline, a creek or river or a coastline, which is, or is roughly aligned with the intended route.

If the handrail is offset to one side and not exactly in the right direction it still may be worth detouring to, especially if it makes the going easier. Creeks or gullies as handrails must be assessed on their individual merits, as often they are not easy going. It may be possible, however, to travel parallel to them, just out of the denser scrub or just off the steepest ground.

Aiming off (intentional error)

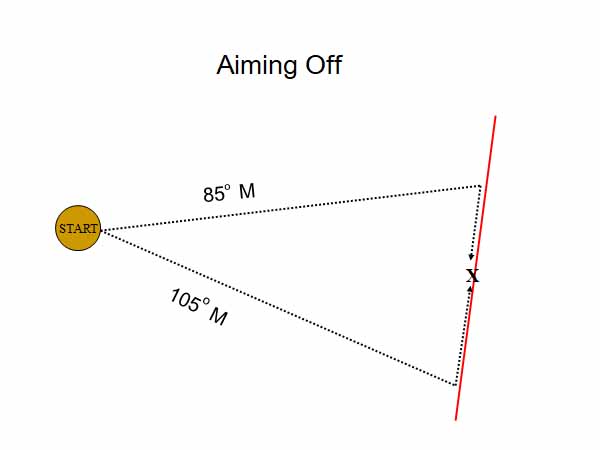

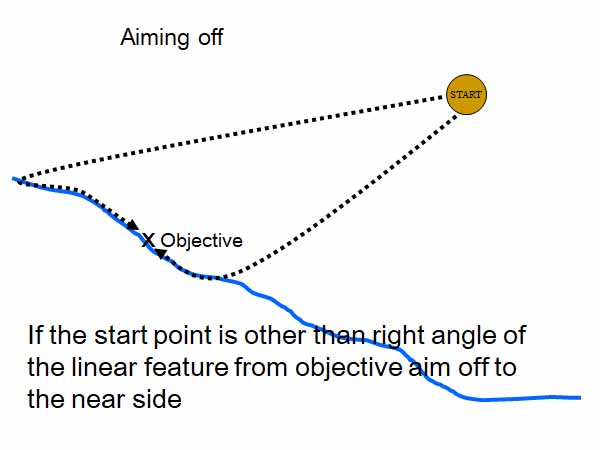

Aiming off is a technique used to find an objective on a linear feature such as a river, mountain ridge, coastline, track, etc, that is being approached from the side.

The navigator deliberately sets a bearing or choses a route that is calculated to reach the river, track or ridge to the right or left of the objective. Thus when the linear feature is reached, there is no doubt as to which way to turn to reach the objective. For example, if aiming off to the right, the group needs to turn left when the linear feature is reached.

The amount of aiming off will depend on a number of factors, but as a guide for average conditions and distances, 10° could be added to or subtracted from the bearing to the objective. The longer the distance over which aiming off will be carried out, the smaller the aiming difference can be provided the bearing can be walked reasonably accurately.

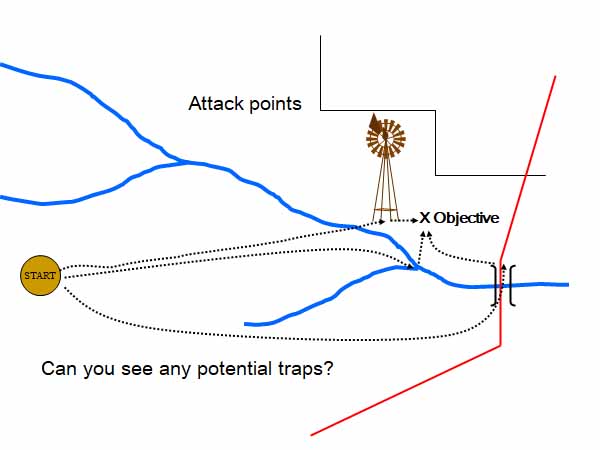

Attack point

An attack point is a feature which is near the objective, but much easier to find. For example, if the destination is a hut in a forest, a definite creek junction or nearby prominent knoll is chosen. First navigate to the easier to locate junction or knoll, and once there the hut will be much closer and hence easier to find, say by a compass bearing.

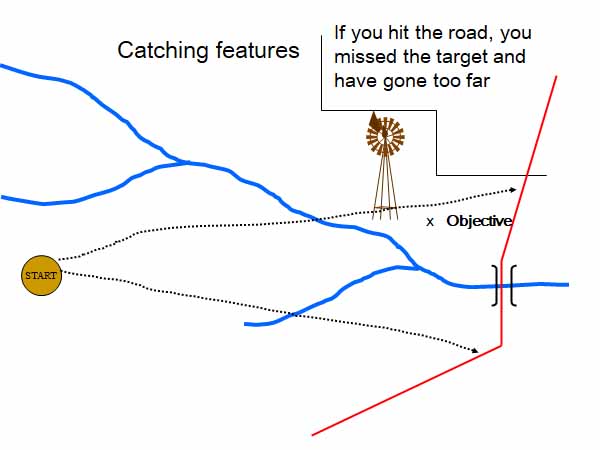

Catching features

Catching features are prominent features which are beyond the objective and should always be noted where they exist. For example, if aiming for a campsite or hut, beyond it may be an area of open private property, or a bitumen road, or a river, or a large lake. If the catching feature is reached it is a clear indication of an overshoot. Obvious catching features will not always be present, but they can be manufactured, e.g. the bearing on some prominent nearby peak.

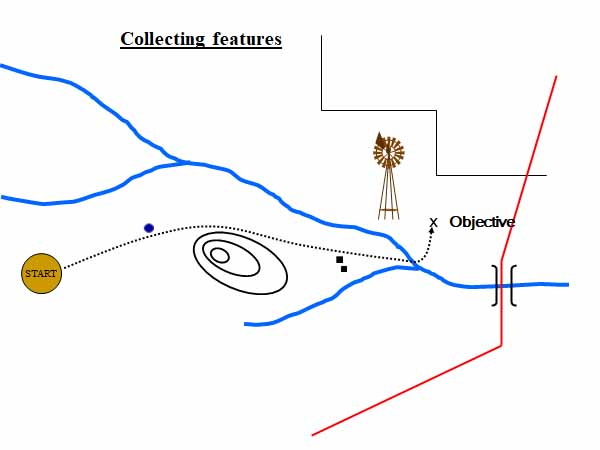

Collecting features

These a prominent features along a route, that can be noted and ticked off as they are passed or crossed. Examples would be a summit, a deep saddle, a creek crossing, a road.

Obstacle negotiation

When walking on a compass bearing, it is usually desirable to dodge around obstacles such as patches of thick scrub or fallen timber to make the best use of open going and then re-position to the original course within a short distance.

The standard method is to use the compass to carefully identify a distinctive feature on the correct bearing a few hundred metres ahead and then walk to it by the easier route.

This method will not work in conditions of poor visibility such as fog or at night.

Estimation of distance travelled

This requires practice to learn to do with a level of accuracy, yet it is one of the most important skills for accurate navigation. To maintain an accurate check on the distance travelled requires:

- regular checks of the time

- experience in estimating actual speed in kilometres per hour

- rules of thumb based on experience for typical group speeds in different conditions.

- calculation of distances from the map. The compass cord is very useful for measuring distance along a winding track on the maps.

See Naismiths rule in Route Planning.

The elapsed time interval may be used in two ways to estimate distance.

The first, and most useful for forward planning, is to:

- scale from the map the distance to the next objective

- calculate the approximate time required to reach it, based on speed of the group.

- predict the time of arrival at the objective.

- check the actual time of arrival. This will help improve the estimate of the speed of the group.

The second, to determine the current location, is to:

- note the time elapsed since the last known feature.

- calculate the distance travelled, based on the speed of the group.

- use that distance to estimate the current location.

Pace counting to determine distance travelled, while widely used in orienteering and by some Rogainers, is seldom used in bushwalking except for short distances in conditions of very poor visibility.

Back bearings

The current position on a map can be determined by using known points of reference, provided some are visible. For example, if at an uncertain point on a lengthy featureless ridge with some identifiable features in different directions to either side which are on the map, those features can be used to calculate the current location. The method is called resection or triangulation.

To perform a resection or triangulation follow these steps:

- Identify a feature which is shown on the map.

- Take a magnetic bearing to that feature.

- Convert that bearing to a back bearing (i.e. either add or subtract 180°).

- Convert the magnetic back bearing to a grid bearing (see Map and Compass Basics)

- Now plot that bearing on the map by drawing a line from the known feature in the direction of the calculated grid bearing.

- Repeat this procedure with two other known features on the map. Ideally the three features should be in different directions.

In theory the result will be a point where the three lines intersect. In practice the result will be a triangle where the three lines meet. If done well, the triangle will be small. The current position lies somewhere within that triangle. Using back bearings to perform a resection or a triangulation always takes some time. It needs to be practised.

Of course, a GPS solves the problem of an uncertain location much more easily.

References and external links

- Which Way’s North (pdf) – Victorian Rogaining Association (an introduction to rogaining, see page 24 onwards)