Reading Time: 10 minutes

Authors:

- Ian Rogers, MMBS FACEM Professor of Emergency Medicine, St John of God Murdoch Hospital & University of Notre Dame Fremantle

- Jenny Brookes, MBBS FACEM MHPE Emergency Physician

Hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a fall in core body temperature to below 35°C. Predisposing factors for the development of hypothermia include:

- Hunger and inadequate food intake

- Fatigue

- Prolonged exertion

- Low body fat (e.g. thin, male etc)

- Low ambient temperature

- High wind chill

- Inadequate clothing (ineffective insulation, unprotected head)

- Wet clothes (rain, sweat) – cotton and denim are especially problematic in this regard

- Inadequate equipment (protection from cold, wind, wet)

- Alcohol (as it both increases heat loss and inhibits heat generation)

- Underlying disease or illness (e.g. diabetes, dehydration)

- Underlying debility (e.g. elderly, frail, anorexic)

- Injury (blood loss, head injury, immobilisation from any cause).

Prevention of hypothermia

Humans’ responses to cold are to reduce heat loss, increase body heat production and seek external heat. The prevention of hypothermia focuses on ensuring these processes can operate effectively as most of these adaptations to cold are behavioural (you can’t really cold acclimatise).

Trip planning

A key part of hypothermia prevention is adequate trip planning, party preparation and sound leadership.

Group members should be fit for the trip and should have adequate rest and nutrition. Dehydration should be avoided. It is preferable to drink cold water than ingest snow or ice, as the conversion of ice to water uses a large amount of body energy.

Groups should be well equipped for shelter in cold or wet conditions. Over exertion should be avoided, as cold and exhaustion in combination predispose hypothermia.

Clothing

Appropriate clothing is essential. There should be insulation worn over areas with large blood vessels close to the surface, such as the head and neck, which have a high heat loss potential.

Wet inner garments should be changed, conditions permitting.

Clothing should be varied according to the weather conditions and exertion levels to stay warm and dry. The effectiveness of clothing in the cold depends on its insulating properties, including when wet.

Clothing should be layered to avoid both cooling and over-heating. Water conducts heat around 30 times faster than air at the same temperature, so wet clothes, including those wet from perspiration, must be avoided.

Denim and cotton are notorious for staying wet and so enhancing heat loss. Keeping clothes dry reduces heat loss by evaporation and conduction. Ventilation is important to allow evaporation of sweat and to keep clothing dry. Windproof outer shells reduce heat loss from evaporation and convection.

Windchill

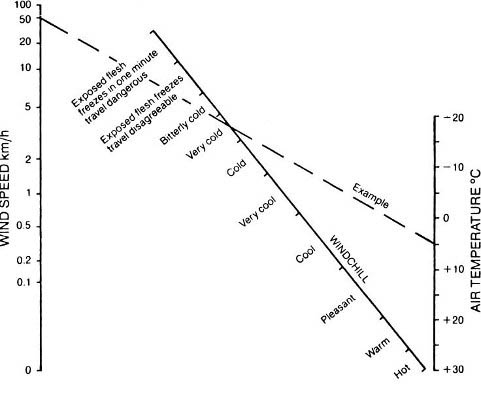

The cooling effect of wind combined with cold should be understood. Windchill charts demonstrate that the rate of cooling (‘windchill’) increases as the wind rises, as shown in the diagram below. This is not a linear relationship – an increase in wind chill approximates the square root of the wind speed. There is no change in actual temperature, but the effect of wind velocity on the rate of cooling for a given temperature is significant.

Recognition of hypothermia

Recognition is based on knowing the signs and observing the patient. The signs may be subtle, so there should be a high level of suspicion of hypothermia in any person behaving abnormally in likely conditions. Patients with hypothermia will often not recognise their own impairment, and so recognition must be done by others. In general a patient who says they feel cold isn’t yet hypothermic (but may be at risk of becoming so). Response cannot be delayed; failure to implement appropriate measures immediately risks the life of the patient.

All group members should be observed, remembering that the occurrence of hypothermia in one member of a group suggests that others may be susceptible. While the body can acclimatise to heat, there is no clear evidence that the body can acclimatise to cold to any significant degree. The combination of exertion and the need to maintain body temperature in a cold environment places a large demand on body energy stores, requiring frequent carbohydrate snacks.

Fitness alone does not improve the ability to withstand cold stress, but physical fitness and good nutrition may reduce fatigue or exhaustion when activity and shivering are required for heat generation, and increase the margin of safety in the cold.

Classification of hypothermia

Accurate measurement of core body temperature is difficult in the field and so assessment is very reliant on clinical signs.

Hypothermia is considered mild if core temperature lies between 35°C and 32°C and profound at core temperatures below 32°C. In most cases of mild hypothermia, the patient is able to rewarm themselves by shivering, provided proper first aid measures are instituted, with prevention of further heat loss being the most important.

However, in severe hypothermia, the patient loses the ability to rewarm themselves, there is significant impairment of brain, heart and other bodily functions, and there is grave threat to life. It is virtually impossible to rewarm such a patient in the field, but further heat loss can be minimised by first aid measures.

Evacuation should be arranged urgently. While the lowest recorded adult accidental hypothermia survival temperature to date is 16°C, the risk of death is high once core temperatures fall below 32°C.

Mild hypothermia

Early signs of mild hypothermia are forgetfulness, loss of judgement and loss of coordination, particularly of fine movements (e.g. use of fingers).

There may be some abnormal behaviour, such as lack of cooperation and apathy. Shivering will occur and may be uncontrollable. Other signs of impaired brain function may occur, such as slurred speech and stumbling gait.

The appearance of hypothermia can cover a wide spectrum, ranging from mild, insidious loss of judgement, which may not be immediately apparent, to the obviously stumbling, forgetful person.

Paradoxical’ undressing may occur; the inappropriate undressing in a hypothermic patient indicates loss of normal protective behavioural responses.

The signs of mild hypothermia may be subtle and easily missed when the group is battling adverse conditions, unless vigilant observation of all group members is maintained.

Profound hypothermia

The loss or absence of shivering in the cold patient is a concerning sign and signifies development of profound hypothermia.

Suspect onset of profound hypothermia when there is marked loss of coordination and marked change in mental function (such as confusion, reduced level of consciousness or coma). Shivering stops and the patient loses the ability to rewarm themselves. The patient will be cold to touch.

Breathing becomes shallow and the pulse becomes faint and slow. In very severe cases the patient may have fixed, dilated pupils, be rigid and unresponsive, and without obvious breathing or pulse; they may appear lifeless.

Signs of life must be carefully checked for, as they may be present but very hard to detect, as discussed later. The cause of death in hypothermia is cardiac arrest; that is, the heart stops.

Management of hypothermia

Hypothermia is a life-threatening condition.

Mild hypothermia alone should not result in death when treated appropriately, but the mortality rate from severe hypothermia is very high. The prime aim in the management of hypothermia in the field is the prevention of further heat loss.

Patients with mild hypothermia can usually rewarm themselves if further heat loss is prevented. Even with special equipment it is virtually impossible to rewarm the profoundly hypothermic patient in the field, and prevention of further heat loss is the prime treatment, while awaiting urgent evacuation.

If hypothermia is suspected, commence treatment immediately. Do not continue but instead seek shelter urgently. Shelter from cold, wind, rain, and snow should be provided by whatever means possible (e.g. tent, snow wall, bivvy bag). The patient must be kept as dry as possible. Attempt to provide a warm environment. Placing several rescuers inside the tent with the patient may help raise the air temperature.

If the patient is sufficiently alert to assist in the process, wet clothing can quickly be removed and replaced with dry, provided that this does not expose the patient to further heat loss. Cutting off clothing may speed this process. This may only be achievable in an environment of warm, still air.

Gentle handling of the patient at all times is extremely important. With more severe hypothermia, or in adverse conditions, removal of wet clothing is usually too risky, in which case the use of a vapour barrier is recommended.

Using a vapour barrier

The vapour barrier approach is the accepted treatment for severe hypothermia in the field.

It involves enclosing the patient, complete with all clothing (including sleeping bag if appropriate), in waterproof material (e.g. space blanket, plastic garbage bags). Creating a vapour barrier wrap can be likened to folding up a burrito. Only the face should remain exposed. Remember to cover the head and neck (keeping the face clear), as these are sites of high heat loss; up to 80% of total body heat loss may occur from the head and neck regions.

Insulation

Ground insulation is essential, and improvisation to increase insulation with clothing or newspapers may be possible.

Warm sweet drinks

An alert patient who is able to swallow may be given warm sweet drinks. Do not offer liquids if they are vomiting.

Heat sources

Heat sources such as chemical heat packs or hot water bottles may be applied to the patient’s neck, armpits and groin. These are sites where large blood vessels lie close to the surface of the body, the aim being to provide heat to the body’s core, rather than the surface.

Body to body contact with a warm rescuer is another heat source alternative in desperate situations. The heat source must be adequately wrapped in clothing or padding so as not to be too hot and not in direct contact with the skin, which risks burning the patient. Particular care must be taken in the semi-conscious or unconscious patient.

The patient should be kept horizontal, as the hypothermic patient is prone to a fall in blood pressure (leading to fainting) if they are placed in an upright position.

Do not allow exertion or massage

Do not allow any exertion by the patient or massage of the extremities, as these increase heat loss.

Ongoing care of hypothermic patient

The patient’s condition may deteriorate in the first few hours following commencement of treatment due to shock or a further fall in body temperature.

Excessively rough handling in treating severely hypothermic patients must be avoided because the heart is very sensitive; rough handling may precipitate cardiac arrest and death.

The gentle, vigilant care of the semi-conscious or comatosed patient is a very taxing task, requiring the assistance of several rescuers.

Once a mildly hypothermic patient is rewarmed, well hydrated and has returned to normal function, then there is no need for evacuation, although care must be taken to prevent recurrence.

If circumstances are such that adequate first aid measures cannot be delivered to the patient with mild hypothermia, then great care must be taken to monitor the patient for further deterioration while walking out.

Any patient who does not respond to the rewarming measures, who deteriorates or who has profound hypothermia must be treated with maximum first aid measures and evacuation arranged urgently.

Resuscitation of hypothermic patients

If breathing is absent, initiate mouth-to-mouth resuscitation immediately.

For hypothermic patients it is wise to feel for a pulse at the carotid pulse for at least one minute, before declaring the patient pulseless and therefore commencing Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR). This is because in severe hypothermia the pulse may be slow, faint and very difficult to feel.

Do not commence CPR if:

- There are any signs of life (be it breathing, pulse, movements). Each of these may be difficult to detect so a thorough search for them is appropriate before commencing CPR.

- There are obvious lethal injuries present

- Chest wall depression is not possible (due to a rigid, frozen chest)

- Any signs of life are present (e.g. pulse, breathing, movement)

- If there is danger to rescuers.

Summary of hypothermic patient management

- Stop at suspicion of hypothermia in any group member.

- Treat as an emergency – seek urgent rescue and evacuation if severe hypothermia is suspected.

- Reassure the patient and check other group members.

- Shelter from cold, wet, wind.

- Handle the patient extremely gently at all times.

- Insulate from the cold, including the ground.

- Provide head insulation.

- Replace wet clothing with warm and dry clothing, but only if the patient is conscious and risk of further heat loss is minimal.

- Use a vapour barrier “burrito wrap” to retain warmth.

- Warming devices (e.g. hot water bottle) should be carefully applied to neck, armpits and groin.

- Wrap the patient in layers (e.g. clothing, vapour barrier, sleeping bag, insulation, tent or bothy shelter).

- Warm the air around the patient if possible (e.g. inside a tent).

- Give no alcohol.

- Allow no activity.

- Do not rub or massage the patient.

- Monitor and record management actions and the patient’s condition.

Ensure that other group members are not placed at risk of hypothermia during care of the first patient. Maintain the morale of the patient and other group members (including self!).

It may be useful to delegate providing reassurance, explanation and comfort to a specific group member.

In summary, for a hypothermic patient always consider that there may be other injuries, particularly if the circumstances are not clear (e.g. finding an unconscious skier). Care of the unconscious patient should follow standard first aid practice.

Other cold-related conditions

Frostbite

Frostbite is the localised injury or death of tissue due to cold exposure. Factors which predispose to frostbite injury are:

- alcohol intake

- type of cold contact (especially contact with cold metal, water or fuels)

- duration of cold exposure

- ambient temperatures below –2°C

- high winds

- humidity and skin wetness

- inadequate protective clothing (e.g. wet clothes, poorly fitting boots or gloves)

- impaired circulation (e.g. constrictive clothing, smoking)

- fatigue, over-exertion

- previous frostbite

- long periods of immobility.

Frostbite often occurs in the setting of a sudden storm, accident, fatigue or alcohol intoxication. Avoid tight clothing and ensure that shoes and socks fit well, with no pressure areas.

Keep the hands and feet dry. Wet skin is more likely to become cold or damaged, and is more susceptible to frostbite. Similarly, modify dress and activity to minimise perspiration. In extreme cold, unless dexterity is required, mittens are preferable to gloves.

Take care handling equipment, particularly wet metal objects and fuel. Group members should have up-to-date tetanus immunisation.

Frostbite occurs on the extremities, such as toes, fingers, nose and ears, with the toes being the most common.

The frostbitten part feels very cold and is usually numb. The area is painless until rewarming. The extremity appears pale, white or mottled blue. In superficial frostbite, tissues below the skin remain soft to touch.

In deep frostbite, the deeper tissues appear frozen solid, and are hard to touch.

Following thawing, there may be a few clear fluid-filled blisters in superficial frostbite and many clear or purple blisters in deep frostbite. The initial treatment of frostbite is the same regardless of the severity.

Management of frostbite

Replace wet and constrictive clothing on the affected limb with loose, dry clothes (e.g. socks and mittens).

Remove jewellery or other items that are restrictive or cause pressure on the skin.

Cover any blisters or wounds with dry, sterile dressings, and apply padding and a splint to the area.

Remember to check for the presence of hypothermia and provide all possible shelter.

When managing frostbite:

- do not prick blisters

- avoid smoking and alcohol

- do not rub with snow or immerse in cold water

- do not apply direct heat to the area

- do not rub or massage the part as this is potentially harmful.

Evacuation should be undertaken as soon as possible if blisters have formed. Self evacuation may be possible if the hands are involved, but frostbite on the feet may render the patient unable to walk.

If deep frostbite is suspected then medical care should be sought urgently.

Rewarming a patient with frostbite

Only rewarm in the field if full rewarming is certain and any refreeze can be prevented.

Field rewarming may be precluded by adverse conditions or lack of appropriate equipment, such as an adequately sized container to provide a bath for the affected part. Rapid rewarming is undertaken by immersing the affected part in gently circulating, warm water at 40–42°C. (The rescuer should test the water with an elbow if a thermometer is not available.)

Rewarming usually takes 30 minutes, and the whole of the thawed part, including the tip, should appear soft and red. Pain may be very severe, and is difficult to manage with oral medications.

Blisters may appear after thawing and should be kept intact. The parts should be gently dried, sterile gauze placed between the toes or fingers, then the part padded, wrapped and insulated to prevent injury or refreezing. Elevation will help reduce swelling.

Avoid refreezing. The damage caused by refreeze after the thawing of a frostbitten part is much greater than the damage caused by delayed thawing.

If the patient must evacuate by walking through snow, then that is best undertaken before thawing frostbitten feet, rather than risk refreezing after thaw. In addition, extreme pain may occur during rewarming, which may render a person previously capable of walking on frozen feet incapable of self evacuation on thawed feet. Spontaneous thawing may occur during evacuation depending on the conditions.

The decision to undertake rewarming in the field needs to consider the:

- expected time until evacuation or rescue

- likelihood of spontaneous thawing

- rendering of an ambulatory patient incapable of walking by rewarming

- ability to rewarm in the field, given the equipment available.