Reading Time: 6 minutes

Route planning is fundamental to ensuring that a trip meets the expectations of the group, providing enough (but not too much) challenge and making the most of all the available opportunities for enjoyment rather than just plotting the shortest route from A to B.

General Considerations

A realistic assessment of the capabilities of the group and its weakest members is essential. This includes determining the skills, fitness and experience of group members, the suitability of their equipment and deciding on group size based on the proposed trip.

Careful route planning ensures that potential hazards are identified and addressed. When considering a route, check for navigational challenges that may arise especially in bad weather.

As part of the planning process consider the following:

- Season. What is the best time of year to undertake the proposed trip? (e.g. autumn colours, seasonal wildflowers, favourable temperatures, humidity).

- Weather. What are the typical weather conditions? What range of weather is possible? (e.g. cyclones, blizzards, extreme heat, strong winds, tides, floods).

- Safety. Is the proposed route safe? (e.g. sheltered campsites, safe river crossings, steep/exposed climbs or descents, scree slopes, exit points)

- Bushfire. Is the area subject to extreme fire danger?

- Tracks. What are the track conditions? (e.g. tracks may be overgrown)

- Terrain. What type of terrain will be covered? (e.g. steep climbs and descents, soft sand, mud)

- Obstacles. Are there obstacles which may take time for negotiation by the group? (e.g. river crossings, fence lines, cliffs, high tides)

- Direction of travel. Is one direction better than the other? (e.g. avoid headwinds, get the best views)

- Water. Where will drinking water be reliably found during the trip? How much will have to be carried and when?

- Campsites. Are campsites in appropriate locations and of suitable size?

- Daily stages. Can long sections be split or shortened if needed? (e.g. due to prevailing weather or injury/illness). Are some rest days appropriate?

- Altitude. Is the altitude gain and loss within the capability of the group?

- Personal Goals. Is there time to ‘bag’ an important peak or to stop and look at wildflowers?

- Environmental impact. Is the area particularly sensitive to environmental impact, and hence should the group be smaller or the route be changed?

- Special arrangements. Are pre-placed food and/or water drops required on an extended or desert trip?

Off Track Considerations

Off track trips require a high level of navigational skill. Demands on the group increase markedly in difficult terrain.

- Rock scrambling and negotiating scree slopes. Requires each group member to have a high skill level.

- Spurs. Navigating up a spur is easier than going down. When travelling down spurs branch, requiring particular attention to ensure the correct spur is followed.

- Gullies. Generally best avoided, but travelling down is easier than going up because side gullies converge.

- Rivers and creeks. Can provide obvious and useful routes if not choked with vegetation.

- Vegetation. How dense will the vegetation be? Increased prevalence of bushfires has led to dense, impenetrable re-growth in some areas.

- Coastal trips. Research tides, prevailing and forecast winds, soft sand, rock and cliffs, estuary crossings, fresh water availability, impenetrable scrub.

Snow Considerations

Winter trips in alpine areas have specific challenges for a group.

-

- Snow cover. Will there be sufficient snow cover for the entire route?

- Navigation. Very difficult in whiteout conditions.

- Weather. Blizzards, dangers including icy slopes and avalanche risk.

- Clothing. designed for winter conditions is essential, particularly good quality wet weather gear and sturdy boots.

- Equipment. Intended for four-season use essential, particularly tent, insulation mat and sleeping bag rated to negative temperatures.

- Snowshoes/Skis. Walking in snow as if on a bushwalk is a slow and difficult way to travel and not recommended. A large group may find some value in stamping a track, but this is difficult over prolonged periods.

- Snow-caves/Igloos. Are proposed campsites potentially suitable for snow-cave digging or igloo construction? A four season tent must also be carried.

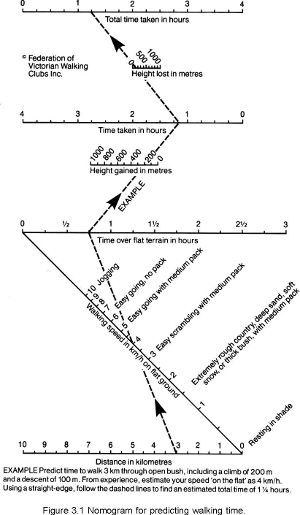

Predicting walking time – Naismith’s Rule

The distance a group can cover is commonly overestimated. This can be avoided by planning the route before the trip and using the guide below for predicting travelling times. The number of variables involved in predicting walking times makes it difficult to provide one rule which works for all people in all conditions.

The following ‘rule’, often referred to as Naismith’s Rule, has proved suitable for Australian conditions.

For an average walker with a medium pack, allow one hour for:

- Every 4 km – easy going terrain (e.g. track, open forest, firm sand)

- Every 3 km – easy scrambling or light scrub

- Up to 1½ km – rough country, deep sand, soft snow or scrub.

Then add:

- One hour for every 500m climb

- One hour for every 1000m descent.

This rule has been developed for an ‘average’ group. For very fit and experienced walkers, reduce the total time by one third, and for larger, less fit or less experienced groups, this rule may be optimistic.

Several bushwalking clubs recommend a variation of this rule, with one hour for 4 km of easy going, 2 km of rough track and 1 km off track. The time allowed for rise and fall in elevation accounts for slower travel and fatigue during both climbing and descending. Time must be allowed for rest and meal stops, and remember that the group will be slower at the end of the day.

Figure 3.1 above can be used as a quick reference for applying this rule.

This rule is not directly transferable for ski touring, as strengths and weaknesses in skiing skills greatly affect the travelling speed of a group on skis. The fastest travel can be very quick, up to 8 or even 10 km per hour, but in difficult conditions, progress can be slower than walking. As a result leaders will have to apply their own estimates, based on skill levels of the group, and knowledge of the area and terrain.

Escape routes

An escape (or exit) route offers a safe alternative to the planned route that may be used if:

- there is injury or illness in the group

- the weather does not allow the group to continue safely along the planned route

- the group is struggling with the trip

Ideally an escape route leads to a point offering vehicular access, although this may not always be possible. An escape route may simply be an easier alternative route.

Some trips will not have escape routes. In these circumstances the only practical options are to decide to return to the start or to persevere and continue to the intended finish.

A trip with no escape routes requires a higher level of confidence that the group can complete the trip.

Planning car shuffles

When the start and the end of a trip are not at the same place, a car shuffle can get everyone to the start, while leaving enough cars at the end for drivers to return to the start to retrieve vehicles.

Practical considerations dictate how car shuffles must be done (e.g. locations for an easily found Friday night camp may be limited), but planning can keep car shuffles simple and efficient.

People are usually keen to start a trip and prefer not to wait around while drivers do a car shuffle. However at the end of a trip most people are content to wait for cars to be collected.

The best way to arrange a car shuffle is for the whole group to meet (and set-up Friday night camp) at the location where the trip is planned to end. The group then drives to the start using as few vehicles as necessary. This leaves the remaining vehicles at the end so when the trip is over the vehicles left at the start can be retrieved.

When selecting parking spots check:

- for overhead branches or dangerous trees

- that cars are parked on firm ground

- that cars are parked facing downhill in snow or if snow is expected in gear with handbrake off and wheels chocked

- no valuables are left visible inside

Route-plan cards

Preparing route-plan cards is an optional method for documenting the stages of a trip and expected times. They are a handy resource but can take some time to prepare.

To be useful, cards should break the intended route into logical stages. For each stage, list distance, estimate of required time, ascent and descent distances and brief information about the type of terrain likely to be encountered.

Walking time can be predicted using Naismith’s Rule, either by calculation or by use of the chart in the table below (an example route-plan card for an afternoon).

| Stage | Objective | Grid reference | Bearing | Km | Height + & or – | Terrain | Stage Time | E.T.A. & Remarks |

| PM | At Consett Stephen Pass | 220772 | Lunch till 12.30pm | |||||

| 1 | To Mt Tate | 213758 | 192°M | 1.7 km | +140m | Rough ground & snow grass | 1 hr | 1.30pm |

| 2 | To Mt Anderson via Mann Bluff | 195740 | 3 km | +180m -240m | Picks up old rough fire trail | 1 hr | 3.15pm | |

| 3 | To Mt Anton | 190725 | 1.5km | +120m -140m | Clearer old fire trail | 50 min | 4.05pm | |

| 4 | Camp in Pounds Creek valley | 190720 | 230°M and 152°M | 0.5km | -100m | Into saddle & to valley to choose a campsite | 15 min | 4.20pm |

| Totals | 6.7km | +440m -480m | 3hr 50min |

Example route plan card